I had to travel to Alliston, Ontario (not too far from Toronto in terms of distance) over Memorial Day weekend for a conference. I took the Friday prior to the weekend off so D and R and I would get at least 2 days together as a family, and we were fortunate enough to get some great weather – sunny, 70s, etc.

Sunday I packed my bags and flew to Buffalo. From Buffalo I rented a car and drove to Alliston (about 2 hrs and 45 minutes, but thanks to picking the slowest possible line at the Queenstown-Lewiston bridge border crossing it took another 30 minutes to make it to my destination). Why not just fly into Toronto and save the drive? Good question. As it turns out, flying to Toronto was 4x the cost of flying to Buffalo, and that was flying indirectly, too. If I wanted to go direct, it would have cost me $2000 vs. $300 for Buffalo. No, I did not mistype the zeroes in that last sentence. Pearson is just one of the most expensive airports around, and for the third time this year I’ve chosen to get to Ontario via Buffalo rather than fly directly there.

Anyway, the conference was fine; it turns out that you don’t need to get far outside Toronto (the 3rd-largest metropolitan area in North America) to find it looking a lot like my old home in central California: fairly flat, lots of farmland, low population density, and a shiny new Wal-Mart rising up out of nowhere.

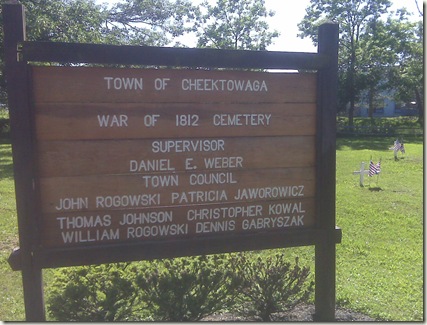

Today, I left Alliston just before 1 PM and made great time back to the border. Since my flight wasn’t for four more hours, and Buffalo is pretty easy to get around, I decided to visit a few historical sites. I already had my mind set on visiting a site that had caught my eye via Google Maps the last time I was searching for the Buffalo Airport: a cemetery dedicated to the War of 1812, hidden behind the airport itself on Aero Drive. I’ve always been fascinated with older cemeteries in general, but this had the added allure of (1) being convenient to my final destination of the airport and (2) since I’d missed Memorial Day while at my conference in Canada, I could pay my respects here instead.

But sitting at Customs waiting to cross the border, I realized I had more time than I had planned, and I could probably do more than just visit the 1812 cemetery. I decided to I’d try to locate something I’ve wanted to see for many years: the marker identifying the spot where President McKinley was fatally shot in 1901. I knew this was in Buffalo, and thanks to my BlackBerry and Google, I was able to find an address for my GPS pretty quickly.

As it turned out, you didn’t need to stray far from the hightway (which I had to take en route to the airport anyway) to find the right spot. McKinley was shot by anarchist Leon Czolgosz in the Temple of Music, a grand but temporary structure built for the Pan-American Exposition, a world’s fair-type event held in Buffalo that year. Here’s a panoramic nighttime view of the buildings as they were at the Exposition:

This area looks a lot different today – in fact, it’s a residential neighborhood. Fordham Drive – where the marker is located – is a totally unremarkable, middle-class street, part of a development of similar-looking streets and homes. In fact, were it not for Google, I probably never would have found the marker, which is a plaque affixed to a stone in the narrow, grassy center strip of Fordham drive.

From Fordham Drive, I headed back to the airport to visit the War of 1812 cemetery. It wasn’t hard to find; it’s on a winding, narrow road behind the airport, sandwiched in between a number of nondescript industrial and/or city-owned facilities.

I had learned ahead of time that the cemetery contains 205 American and British war dead who had met their fates in a nearby military hospital c. 1814-15. Almost all died of dysentery and diarrhea. Thanks to the miracles of modern medicine – and especially antibiotics – we forget how the biggest killer in war used to be infection, not wounds. Even in the Civil War and WWI, disease and infection took a tremendous toll on fighting forces, turning even minor wounds into death sentences for thousands of young men. The quality of medical care didn’t matter; Presidents Garfield and McKinley both died of wounds and resulting infections that modern medicine could have patched-up quickly. One historian thinks Garfield could have been back to work the very next day had he been shot today. Instead, he spent 3 months slowly dying of terrible infections.

It’s a small cemetery; I took this photo near the outer fence looking back towards the road.

What was the “War of 1812”* about? We learned about this in high school, but it didn’t make much sense then and it doesn’t really now, either. Unlike the Revolution or the Civil War, it’s not a war that figures much into the modern American narrative, and unlike those wars you can’t explain it with one sentence. The Revolution: “We want independence.” Civil War: “Slavery is bad”. War of 1812: “The British were mistreating sailors and we thought Britain was arming Indians and Britain was fighting France and we were considering conquering Canada and…”.

* A misnomer, as the war ran from 1812-1815.

In the end, the war resulted in no territorial gains and didn’t do much to resolve the grievances that sparked it. As a teenager, I once spent a day sightseeing in San Francisco with a nice Canadian couple, one of whom was a history teacher. He explained to me that Americans don’t like to talk about the War of 1812 because we lost it. I also learned then that Canadians believe that the war was primarily about conquering Canada (though contemporary American sources indicate that the US likely wanted to capture Canadian territory to use as bargaining chips with the UK, not to keep), and that their successful effort (as a British colony) to repel us was instrumental in forging Canadian’s identity and ultimate independence. Wikipedia has decent pages discussing some of the war’s causes and its outcomes.

Anyway, other than giving us future presidents Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison and the “Star-Spangled Banner”, looking back almost two hundred years later it’s hard to see how the War of 1812 changed anything, other than fill this cemetery and many others. I wonder what sort of commemorations we’ll see over 2012-2015, as the 200th anniversary of key dates and battles from the “War of 1812” come around. I don’t expect it will be like 1976 again.

In the meantime, this Memorial Day, it made me glad to see these soldiers commemorated with new flags and fresh flowers.

1 comment:

Fascinating post, Phil. I like the McKinley marker in the median.

Post a Comment